Kafka: a Distributed Messaging System for Log Processing

Summary of Kafka: a Distributed Messaging System for Log Processing

Apache Kafka is a system for streaming logs with the aim of providing high throughput over strict guarantees around delivery. This was an interesting paper to read ~13 years on, as Kafka has become more and more ubiquitous in system design.

Design

This paper presents Kafka as a relatively simple system, consisting of brokers and consumers. Brokers receive messages from producers. Consumers poll brokers for messages that they care about, which are broken up into topics. Messages are opaque byte strings, allowing consumers to define their own formats. LinkedIn, for example, used Avro encoding, a binary serialization format with a versioned schema1.

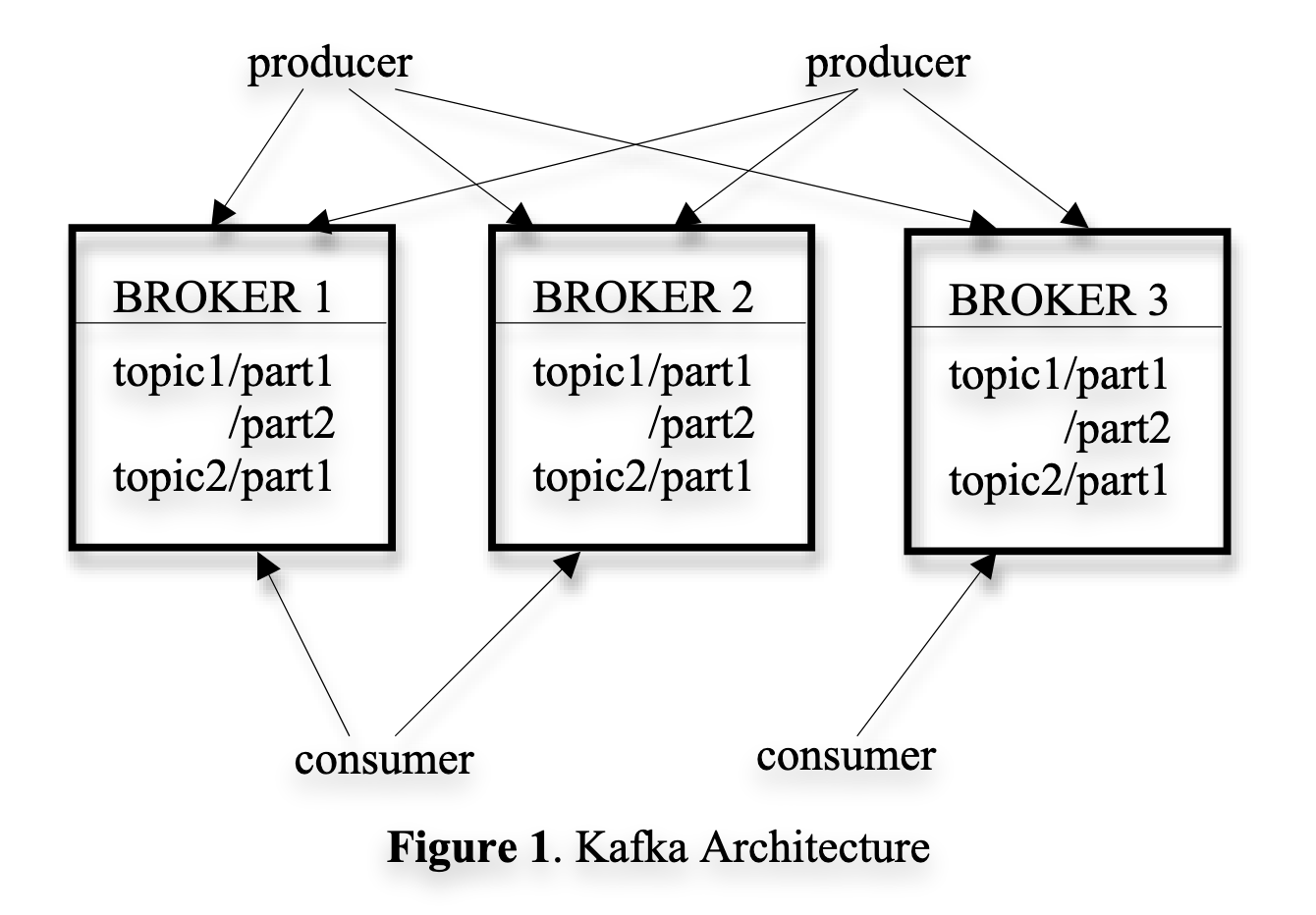

Producers send messages to brokers on particular topics. To distribute load across the nodes, topics are sharded into a number of partitions. Each broker stores one or more of these. Consumers subscribe to a topic by creating 1+ message streams, which each provide an iterator over a stream of messages. Producers can publish a message to either a randomly selected partition, or one determined by a partition key and a partition function.

Let someone else do the hard work

In a few key areas the Kafka developers chose simplicity over complexity in their design, letting someone else do the hard work. This first comes up in the caching (or lack of). They decided to rely on the file system’s page cache instead of caching messages in memory. This has the benefit of avoiding double buffering as well as maintaining a cache between broker process restarts. It’s also simpler to implement and maintain.

Similarly, the developers use the sendfile API to eliminate additional copying on the host. This eliminates 2 buffer copies and 1 system call from a standard approach of sending bytes. This adds up to make Kafka more efficient for throughput.

Instead of organising their own consensus mechanism, Kafka uses Zookeeper for the coordination primitives. This saves reinventing the wheel and keeps the coordination of the system much simpler. Zookeeper mimics a simple file system’s page cache for an API. Paths can be created, have their values set, read, or deleted. Nodes can register to watch a path - meaning a watcher can be notified when the children of a path or its value have been changed. This is used by Kafka for nodes to know when they need to reconfigure.

Paths can also be created as ephemeral, so when the client that creates them disappears the path is automatically removed. By offboarding the complexity of this management to Zookeeper, Kafka again priorities simplicity. Instead of having a centralized main node, the consumers and producers can coordinate in a decentralized way.

Whenever brokers or consumers are added, a rebalancing process is triggered, which spreads the partitions of a topic over the new set of consumers. This is a pretty simple algorithm that runs determinastically on each consumer. Because Kafka only guarantees “at least once” delivery, there’s no real correctness issues that crop up here. But it’s important for developers to be aware that they should implement their own idempotency mechanism if its needed.

Pull vs Push

Kafka operates on a “pull” model for messages, meaning consumers are in charge of the state necessary to pull messages. Each message is stored in memory in the broker while being identified by its memory offset in the log. Logs are partitions of topics implemented as a set of files , each split into roughly the same size.

Instead of giving each message a unique ID, it is identified by its offset in the log file. This is a pretty interesting implementation! It means that the brokers have much less state or information to manage for each message. Consumers start reading messages from the queue, and request the next message by sending the end of the offset they got to. This means that the brokers don’t need to store any state for consumers, they can just feed them the next messages when requested. Another benefit of this is easy checkpointing. If a consumer fails while processing, it can pick up from its last successful checkpoint.

To trim messages, brokers wait for a specific time period, e.g., 7 days. This allows replaying messages over a longer term for consumers, they can just roll back to an earlier point in the queue. Since message queues are saved to files on the brokers, the only added pressure is to disk utilization – which is a lot cheaper than memory.

Why did Kafka become so successful?

I struggled to find any hard data showing the market adoption of Kafka aside from this 2023 Stack Overflow survey where 10% of professional devs reported using it - however that still put it behind RabbitMQ at 12%. There are a lot of articles claiming that Kafka has ‘won’ the message queueing space, and it certainly seems to be used more and more each year, either as a system or a compatible protocol.

There’s probably a lot of people who are more authorised to draw conclusions here than I am. From my understanding, the simplicity of Kafka seems really advantageous. As an API, it’s super simple to work with. You have a continuous iteration of messages which simply hangs when waiting for new ones along the stream. It’s also quite powerful for development. Thanks to the pull model, consumers can replay messages for up to a configurable time limit. This means from an operations standpoint, it’s much simpler to re-read a queue than it is to re-push a queue of messages (as you would in the case of SNS).

The performance benefits of this approach are pretty clear from the paper, at least against the existing top log processors of the time. Since 2011 a number of other data streaming services have emerged, both open and closed source. Kafka’s by no means the only option, but it’s a good example of what the authors put forward: by having a specialized system you can get a good deal of extra performance.

-

I think whatever format you use, versioning or a schema definition is a pretty good choice to have! The paper describes a system where producers and consumers could load the schemas from a lightweight schema registry, which is neat. ↩