Anvil: Verifying Liveness of Cluster Management Controllers

Summary of Anvil: Verifying Liveness of Cluster Management Controllers

Wouldn’t it be nice to write some software and confidently say that you know it’s right? That, as long as some assumptions about the world hold, it’s going to do exactly what you want it to, no matter what strange permutations or combinations of failures happen. In broad strokes that’s the promise of formal verification and proofs in software.

This paper, in particular, is about formally verifying controllers. More specifically, how to verify liveness for Kubernetes cluster controllers. While the researchers start there, I think their contributions are more broadly applicable for other control plane architectures too.

What’s TLA?

Let’s start with a quick diversion/refresher, feel free to skip if you already know! TLA stands for temporal logic of actions. It’s a way of thinking, step by step, how things change over time as the result of actions. Leslie Lamport came up with the field as a way to describe concurrent programs in a formal, logical way.

We use formal methods like TLA to be able to make concrete mathematical statements about things that we can then prove or disprove. Something like “the ground is dry” is a logical proposition about the world. If then an action happens like “it rains” we can know that in the next state “the ground is dry” is false. TLA allows us to draw these same kinds of logical conclusions about concurrent systems.

It’s really useful when we want to describe properties of systems. These could be safety properties, or liveness properties. A safety property says that our system doesn’t do a bad thing, while a liveness property says that our system eventually does a good thing, or the thing we want it to do. Liveness is a tricky thing! Safety properties are usually easier to prove because a system that does nothing can be perfectly safe. Liveness properties require the system to keep making progress towards a goal.

What does this paper provide?

This paper provides a property called eventually stable reconciliation (ESR). They claim that this property precludes a lot of bugs in controllers. It also presents Anvil, a framework for developing kubernetes controllers and verifying that they meet this property. They then use Anvil to verify three Kubernetes controllers and show they have comparable performance to their un-verified counterparts.

ESR is a TLA formula, it’s a statement about a system that can be expressed in TLA. It essentially says that if what the controller wants stops changing, then the system should eventually reach that state.

That seems super reasonable as a goal to me! Intuitively, if a controller is able to update a system to match its desired state then it seems like it’s doing its job. If you don’t have familiarity with controllers or control plane software, you can think of them as being like a thermostat. You set some kind of desired state through configuration (turn the thermometer to 20C), and then the controller makes adjustments to the environment (turns your central heating on/off) while monitoring for changes (checking the current temp) until its desired state is reached.

In the case of a Kubernetes controller, this looks something more like creating service configuration files, or spinning up containerized nodes. The overall principle is the same, but the amount of input or ongoing state increases, and the number of ways in which things can go wrong multiplies.

Formally ESR is represented by the TLA formula:

\(\forall d.\Box(\Box \text{desire}(d) \implies \Diamond \Box \text{match}(d))\)1

This asserts that for all desired states $d$, if the controller always desires $d$, then eventually $d$ will always match the current state. It seems clear that this will prevent a whole range of bugs that prevent the controller from moving towards its goal.

How do they prove things?

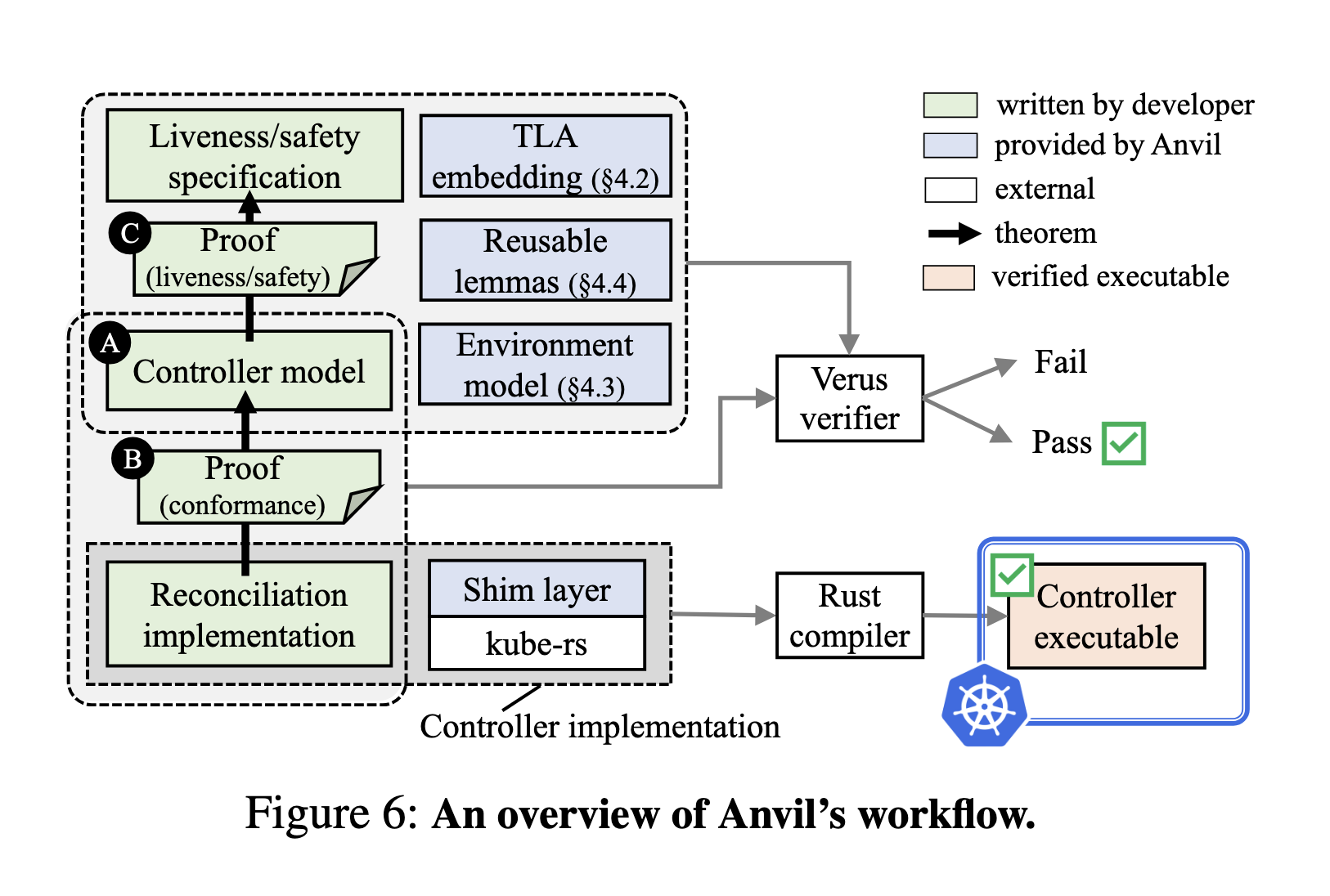

The authors use Verus, a language that allows writing proofs in the form of preconditions and postconditions. Verus leverages Rust’s type system and reduces the problem to an SMT-solvable form. The team extended Verus with a set of simple temporal logic constructs to handle the temporal aspects of their proofs.

The advantage of using Verus is that it allows for modular proofs, breaking down complex properties into smaller, more manageable pieces. This approach makes it easier to reason about and verify complex systems like cluster controllers. Like Dafny, and in contrast to a model language like TLA+, it allows verifying the actual code that you run in production.

The Anvil toolkit provides a good deal of work towards proving ESR for Kubernetes controllers. Proving implementations with Anvil is still a manual process, you still have to write proof code to go with your implementation, but Anvil does provide a lot of handy looking lemmas2 to help.

By applying their ESR property and proof methodology, the authors were able to identify and fix bugs in existing controllers that had been missed by extensive testing. This shows the power of formal verification in catching subtle issues that can be nearly impossible to uncover with traditional testing.

The Future

A big part of why I find this exciting is that it shows a future where more and more of our software is written proof first. With projects like this, it doesn’t seem hard to imagine a world where we start our software with a given proven core and then extend it to match the service at hand. I think this could be extremely powerful for Control Plane software where the problems are relatively common and abstractable: identify what’s wrong, make changes to fix it.

We’re already seeing other aspects of software trend in this formally verified direction. The AWS crypto team have delivered huge speed improvements by formally verifying RSA. By building on the foundation of a correct solution they were able to make more aggressive optimisations.

To be a bit more pedantic, I see this happening for software at the largest scales. At AWS scale events that would be one in a billion are happening every hour. Formal correctness can help eliminate these. A big benefit from that is that, much like with testing, formal verification can give teams the ability to make big changes more confidently. If you know that you have a process to catch issues, it’s much easier to be bold in making big changes.

-

If you’re unfamiliar with TLA, $\forall$ means “for all”, $\Box$ means “always” (in the future) and $\Diamond$ means “eventually”. ↩

-

A lemma (not a lemming) is a reuseable bit of logic that you can use to prove something else. It’s like a useful function that can convert from thing to another. In the case of proofs, if you want to prove some statement $C$, and you know how to prove that $A$ means $B$ is true, it’s really handy to have something that shows that if $B$ is true then so is $C$. That would be an example of a lemma. ↩