MRTOM: Mostly Reliable Totally Ordered Multicast

Summary of MRTOM: Mostly Reliable Totally Ordered Multicast

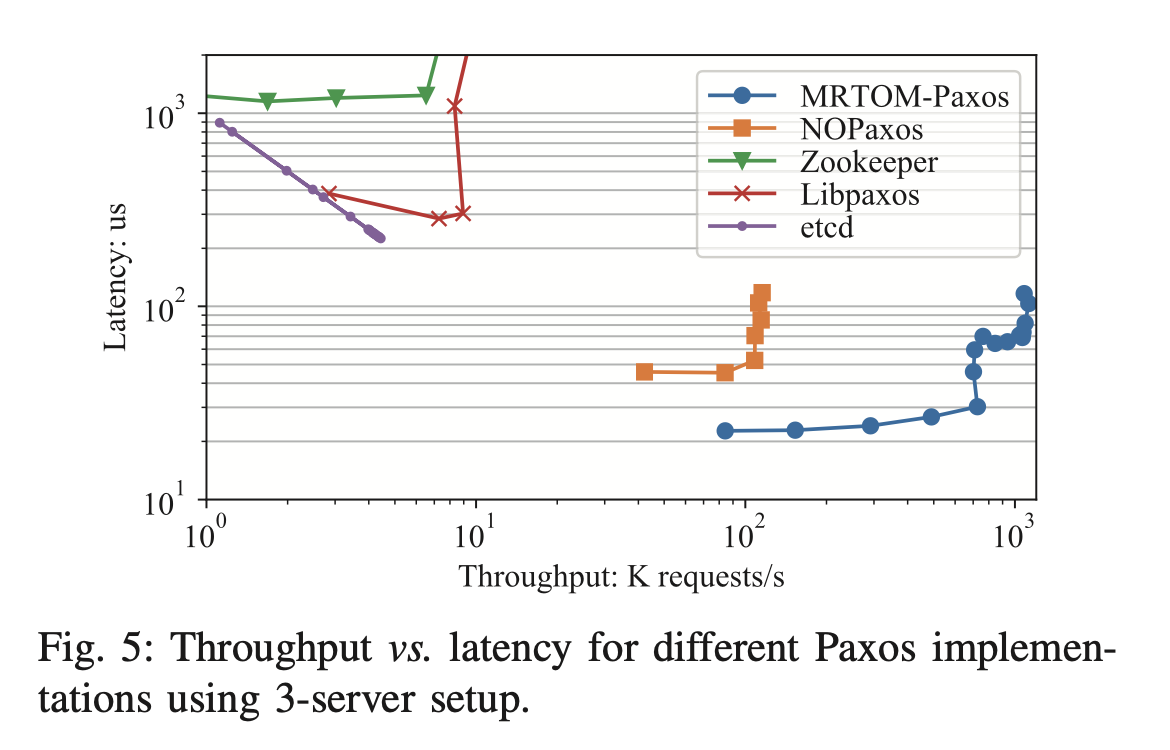

This paper is about building a network primitive to speed up consensus protocols. Like other papers in this area, MRTOM builds on the fact that network ordered protocols can have much higher throughput than standard consensus protocols. MRTOM takes this one step further by offloading not just packet ordering, but also the fast path of consensus protocols to programmable switches.

The consensus problem

It’s probably a good idea to have a quick refresher on what consensus problems are, and why network ordered protocols can be faster.

Broadly, the problem of consensus is agreeing with a group what’s happened. It’s like if you were sending a series of letters to 20 different people in different countries. Some of your letters might get lost or intercepted before they get there, or one of the people you’re sending to might be missing a letter and would disagree with the others on what you’ve said.

Even worse, the letters need to have an agreed order. If you send three messages, the end meaning might be completely different if they arrive in a different order:

- I’ll be arriving at midnight

- I’ll be arriving at noon

- Ignore that last message, the next one will be my new arrival time

These three messages have different meanings depending on when they arrive. We could understand that you’ll be arriving at midnight, or at noon, or we could be unsure of what time you’re arriving at all.1

Without a way of deciding what letters all of the group has received and in what order, we can’t agree on exactly what you’ve said. Consensus protocols like Paxos solve this by ensuring a consensus group agrees on what messages they’ve received and in what order. Typically a Paxos like protocol has a leader that accepts requests from clients, while followers can be used to read committed data or will forward new requests onto the leader. During the process of agreeing on a message, the members of a Paxos group have to send messages back and forth with each other, which takes time, meaning we can process fewer messages and respond slower than if there was just one recipient.

The benefits of having a group of recipients are that because the data is replicated, it is more resilient. One of the recipients could become unavailable, but we’re still able to provide that data when someone comes to read it.

If you know what you’re expecting next, you can act fast

Network ordered consensus protocols, like NOPaxos, exploit the fact that if you have a total ordering for incoming client messages, you can get consensus pretty quickly! Typically consensus incurs a penalty, as a group of servers incur a communication overhead in agreeing what they’ve received. Network ordered protocols make the observation that if you have a monotonically increasing dense ID2 assigned to incoming requests, 1) its very easy to know that you have things in order, and 2) its very obvious if you’re missing a message. If the packets reliably arrive and in order3, then servers in a consensus group don’t need to communicate to agree on what they’ve received and in what order.

Since not doing something is always cheaper and faster than doing something, this lets network ordered protocols do as little as possible. They only have to communicate when packets don’t arrive. This is the separation of the fast and the slow path of network ordered consensus protocols. The fast path is when everything gets there on time and in order, while the slow path happens when a server is missing a message.

The downside of network ordered protocols is they need something to order the messages. Typically this is a single network switch which all messages to the group have to pass through. This switch will then assign each message a monotonically increasing ID. The negative of this is that we’re introducing a single point of failure (bad) and a scaling bottleneck (also not great). There’s no such thing as a free lunch.

MRTOM Design

MRTOM (pronounced Mr. Tom) is based on the observation that the fast path of many consensus protocols “is precisely the reliable, ordered, and acknowledged delivery of messages to a set of nodes”. By focusing on offloading that fast path to the network, the core idea of the paper is to free up server capacity for handling the slow path and other application logic.

MRTOM works by having a MRTOM instance, typically a programmable switch, in between clients and the group of servers running the consensus protocol. This is so far so familiar for the network ordered story. The MRTOM instance provides an ordering for packets, which is then used to speed up consensus.

It differs in two important ways, first that it tries to increase the reliability of delivery by maintaining a loopback of packets. Once a packet has been acked by all servers in the group, MRTOM considers it delivered and can discard it. If it’s not acknowledged within a certain time then MRTOM re-sends the packet.

Second, and more importantly, MRTOM offloads the fast path from the server group, instead running it on the switch through eBPF. This is the main aspect that gives the protocol a big throughput and latency advantage over NOPaxos or other protocols.

eBPF usage

MRTOM allows offloading the fast path of protocols to network switches. They do this using eBPF, which is a way of using Linux kernel capabilities without needing to change kernel source code.

Extended BPF developed from Berkeley Packet Filtering, but is mostly referred to as eBPF now, as the capabilities go beyond just packet filtering. eBPF programs let you run code in the kernel userspace through verified bytecode. This means they can attach hooks to the kernel without recompiling or creating kernel modules. As a result, we can get very efficient program execution as it cuts out the syscall middle man. This in turn cuts CPU & memory overheads by avoiding allocations for packet processing. eBPF also provides means for kernel level programs to have data structures that can interact with user space programs, which is how the switch can then push packets into the slow path.

In the case of MRTOM-Paxos, the fast path is integrated into the MRTOM edge interface. This interface handles aggregating acknowledgement responses from servers in the MRTOM group. Once a majority of servers in the group (including the leader) have responded, the switch sends back an acknowledgement to the client. This aggregation reduces the number of messages and coordination between the client and servers in the group.

Single switch

This paper uses a single switch, much like NOPaxos, which gives a single bottleneck. However, we’ve seen recently other protocols like Hydra demonstrate the ability to scale the number of sequencers while maintaining a total consistent order. I’d like to see a combination of these ideas, to see if there would be a way to merge the multiple sequencer approach with MRTOM’s fast path offloading. My intuition is that it wouldn’t be possible to mix them, given Hydra’s reliance on the receiver’s reconstructing the order.

Summary

MRTOM isn’t a real theoretical advance, but it presents a nice practical idea for increasing throughput and decreasing latency. Doing more at the network level, or even on the server while bypassing the typical overhead of a linux stack with eBPF/XDP, can help us be fast.

However, I’m not sure if the trend of the industry is heading in this direction. While programmable switches have been around for a while, there’s very few commercial cloud operators that will let you use them, and when you do it’s certainly not easy. The trend seems to be to more abstracted and easily fungible hardware, rather than investing time programming switches that will need to be replaced in 4-5 years.