XFaaS: Hyperscale and Low Cost Serverless Functions at Meta

Summary of XFaaS: Hyperscale and Low Cost Serverless Functions at Meta

This paper from Meta presents their home-built Function-as-a-Service system called XFaaS. According to the paper, XFaaS handles trillions of function invocations per day, across hundreds of thousands of worker servers. The paper sets out the system architecture, and talks about how they’re able to achieve some quite impressive hardware utilization at scale.

XFaaS has a number of differences between its architecture and that of public clouds. The biggest differences show up in security, being able to delay function execution, and the ability to globally load balance execution.

One key note, XFaaS may be a hyperscale platform, but it’s clear that it is operating at a drastically different scale to AWS Lambda. In the paper they mention there are 18,377 unique functions invoked every month. AWS Lambda has over one million active customers each month. By the publicly available numbers, there’s at least two orders of magnitude in difference here.

Because of that difference in scale, Meta is able to employ a lot of optimizations in how they deploy the functions. For example, XFaaS preloads each worker with all of the updated function code for a given runtime. That works when you have around 18k functions, but that’s not an optimization that will continue to scale, except by further partitioning workers.

Another place where Meta differs is in the response times. The paper notes that services requiring sub-second response times are rarely served by XFaaS. I can’t tell if this is by choice or a result of the system. XFaaS’s optimization is delayed execution. Each function submitted to XFaaS has a “criticality deadline”, between a few seconds and 24 hours, by which time it should be executed. This means the system can delay execution to smooth out peaks and valleys.

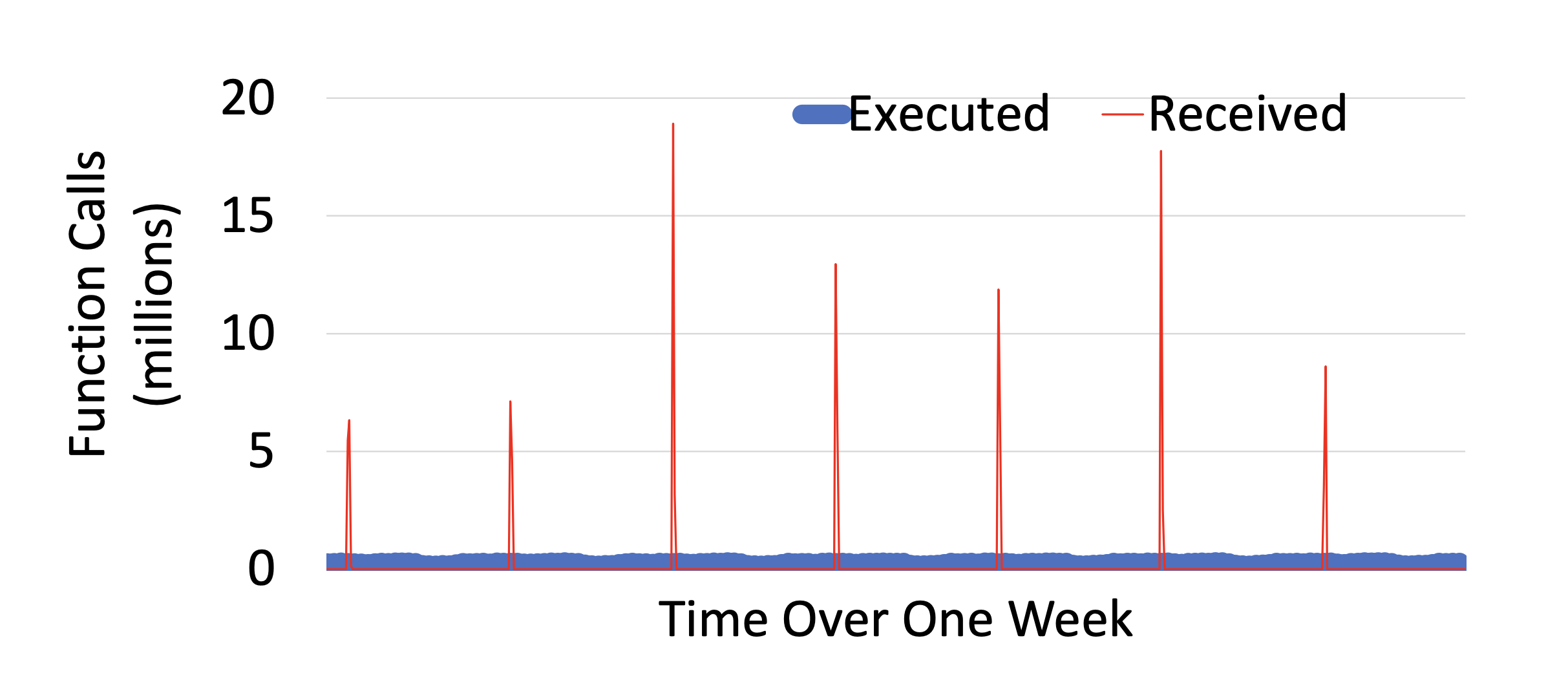

- Figure 4 from the paper shows the function calls executed, vs the invocations received.

However, by allowing functions to be delayed, XFaaS trades off response time for higher hardware utilization. Across public cloud offerings, many many customers rely on (and receive) response times well below a second. As a result, plenty of customers use Lambda, GCP, or Azure Functions to serve live customer traffic. This is not an unsolvable problem of FaaS, but it is a trade off that Meta has decided to make. While they make note that there are no publicly available hardware utilization numbers for other cloud vendors, they comment that their rate of 66% may be “several times higher than that of typical FaaS platforms”. Frankly that’s a ridiculous claim based on anecdotes that I don’t believe would hold up if the numbers were published.

The most interesting mechanism that this paper presents is its backpressure model, where the schedulers are able to dynamically adjust the rate limiting of a function based on exceptions from downstream services. This allows Meta to prevent downstream databases from being overwhelmed by reactively throttling functions. Mechanisms like this do exist in public clouds, event sources like SQS or Kinesis can implement backpressure, however, they’re not as tightly integrated as what the paper describes.

Global load balancing is an interesting mechanism, and an advantage that again seems unique to Meta. Public clouds can’t easily move work from one place to another. First, there’s big concerns with data privacy, with GDPR in place it may not be legal to transfer data between regions. Second, public clouds don’t work well with this! A lot of AWS resources are region localized, endpoints between services differ. A Lambda written for us-east-1 may not run in eu-central-1.

What this paper provides a great example of is the swing back and forth of optimization and generalization in systems at scale. Coupling happens to get some kind of greater performance, for example pre-loading new versions of the functions onto worker hosts. Decoupling comes as the system needs to generalize to handle scale, or new workload types. XFaaS is a system built for Meta’s needs above all, and it clearly works well for their purposes and scale. Is there as much for public cloud providers to learn from? That I’m less convinced.